Defra finally released more details on future farm support in England on the 30th November. Although earlier billed as a consultation, the ‘Path to Sustainable Farming’ document is actually simply a policy statement, with more consultations promised later. As such, it provides rather less detail on some areas of the Agricultural Transition than we might have hoped. The 60-page document can be found at; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/agricultural-transition-plan-2021-to-2024

BPS Phase-Out

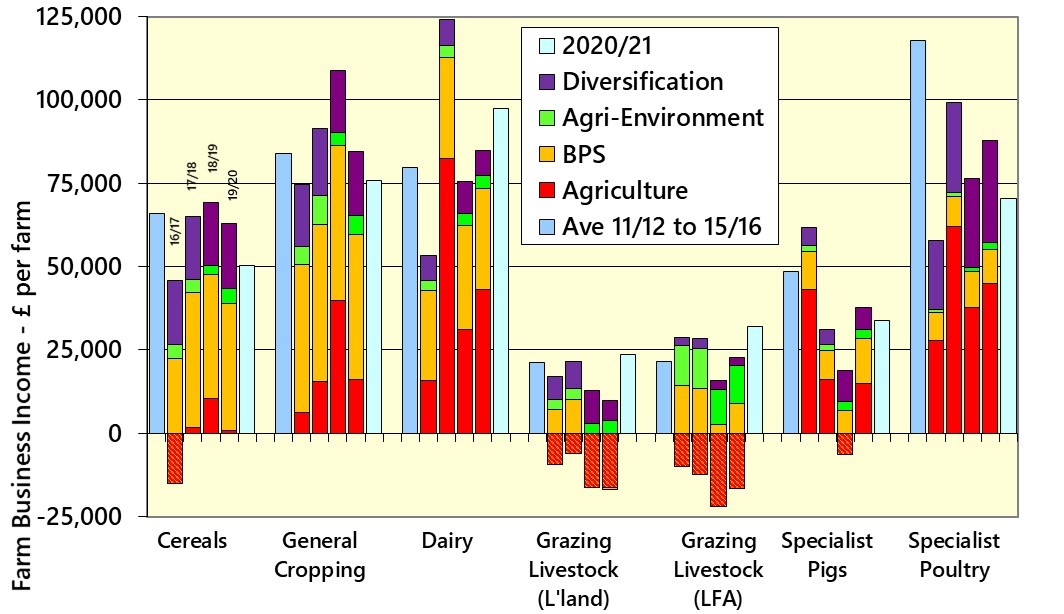

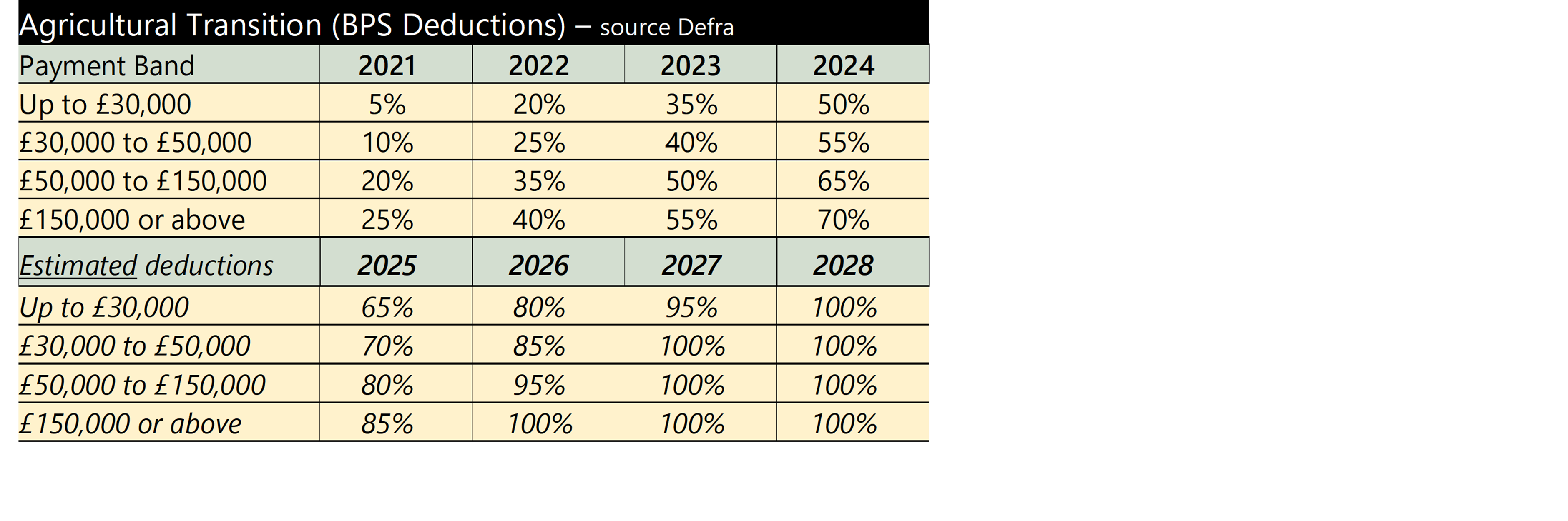

Most English farmers will be primarily concerned with how far and how fast the BPS is to be cut. Only the reductions for the first four years have been announced. This is due to the budget after 2024 not being known as the ‘Funding Guarantee’ runs out after that. The table below sets out the figures that are known, and also our predictions for the final years (based on a simple arithmetic progression).

Note that the figures shown are the deductions rather than the percentage being paid. Also, a reminder that the bands work like Income Tax, so all BPS claimants get the lower deductions on their first £30,000 of claim.

Note that the figures shown are the deductions rather than the percentage being paid. Also, a reminder that the bands work like Income Tax, so all BPS claimants get the lower deductions on their first £30,000 of claim.

The headline point is that at least half of the BPS will be removed by 2024. These deductions are larger than we had thought likely for the early years of the Transition. We had thought that, without ELM launched, Defra would not have a huge need to generate funding. However, it seems that other policy measures (see below) will require significant funding. For those clients who would like to see what this will mean to their BPS payment over the transition period, contact your consultant and they will be able to calculate this for you.

A reminder that from 2021, under simplifying the BPS, ‘Greening’ ends, the requirement to use all entitlements at least once in every two years has also been removed and cross border claims will no longer be treated as one ‘holding’. Those with land in more than one region of the UK will now make separate claims.

Delinking, Lump Sum & Cross Compliance

Delinking will not now happen until 2024 (it was originally intended for 2022). This is the breaking of the link between the payment of direct support and the requirement to occupy land. Presumably, with the link in place, the system of entitlements will continue to operate from 2021 to 2023.

Cross-compliance will also remain in place until payments are de-linked. The consultation states ‘When we delink Direct Payments, we will stop using cross-compliance as the basis for deregulation . . . ).

Despite the delay in delinking, Defra is still looking to offer lump-sum payments in 2022 as an exit scheme. There will be a consultation on both lump-sum payments and delinking in early 2021.

ELM

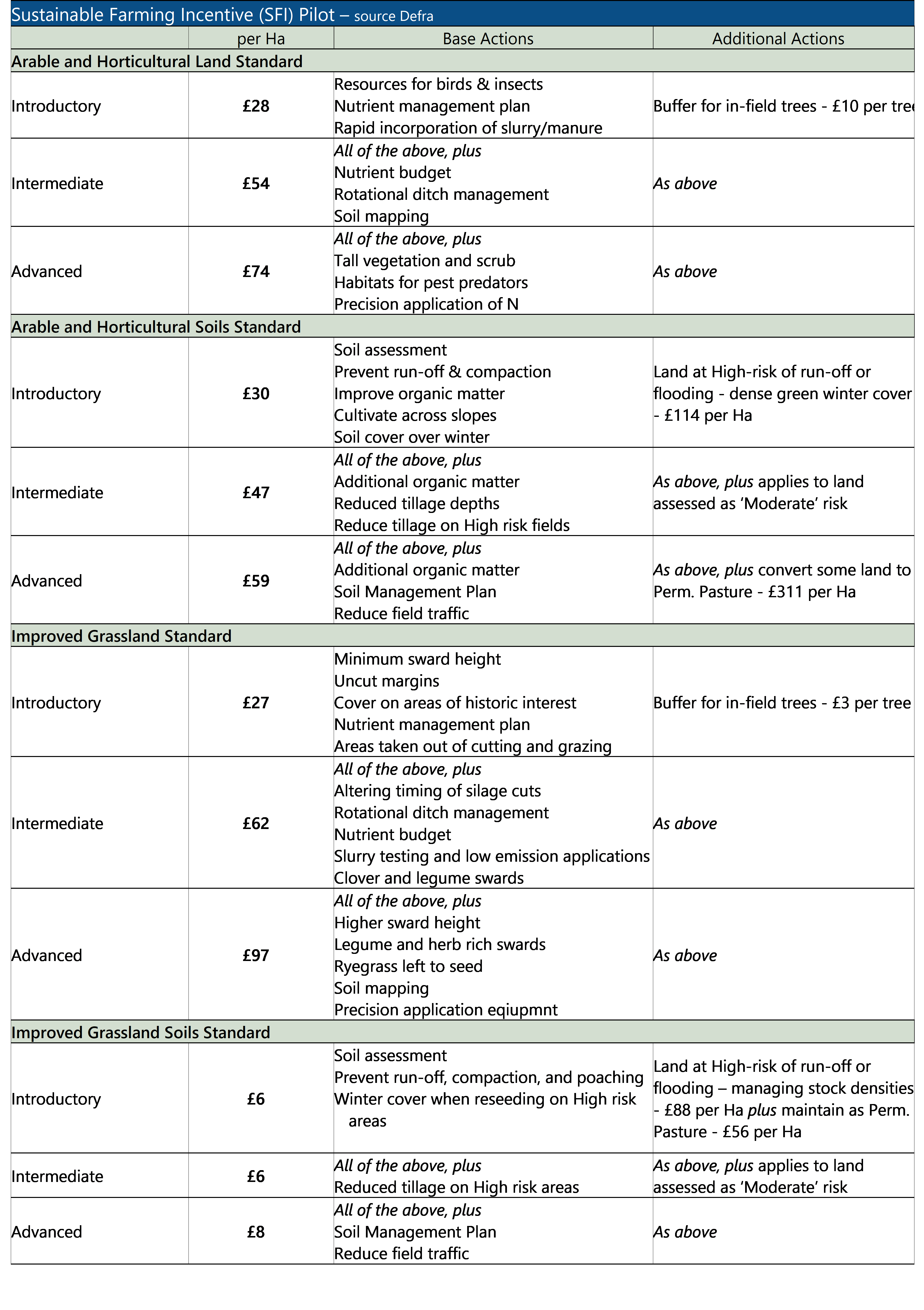

The document devotes 19 pages to ELM and provides a little more detail than what we knew already. The three tier architecture is confirmed with amended tier names;

- Sustainable Farming Incentive: this is broad (and shallow) offer that should be accessible to all farms. It is likely to have a menu of options and be managed online. It could look similar to the previous Entry-Level Stewardship.

- Local Nature Recovery: this will require more intensive management from farmers. It is likely that a whole-farm plan will have to be drawn up (possibly by accredited advisors). The focus will be on rewarding farmers for positive management such as biodiversity, flood management, carbon storage, landscape heritage etc. This will be the ‘core’ of ELM over the long-term.

- Landscape Recovery: this aims to get groups of landowners to work together to deliver widespread change. The focus will be on large-scale woodland planting, peatland restoration and coastal habitats (e.g. salt marshes).

The Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) will open in 2022 – probably with only some elements. It will focus on soils, IPM, and nutrient management. What is learnt in 2022 and 2023 will inform the full launch in 2024 when further elements are added (including boundaries and tree management). Initially it will only be available to those in receipt of BPS, including those already with a Countryside Stewardship agreement. As it is piloted and then scaled up between 2021 and 2024, the aim is to expand the range of options on offer and explore making it available to a wider group of participants which could include smaller farms, horticulture and pig/poultry farms that do not currently receive Direct Payments.

The national pilot for ELM will be testing elements for both the first and second tiers but probably with a greater emphasis on the second – Local Nature Recovery (LNR). Further details on this, and the ability to register an Expression of Interest in taking part in Pilots, should be available ‘early next year‘. Applications to take part in the SFI pilot will be by June 2021 with agreements starting in October 2021. The pilots for the LNR are due to commence in mid-2022. In total, the Pilots are expected to involve 5,500 farmers.

The naming of the second tier as ‘Local Nature Recovery’ clearly points to the importance being given to Local Nature Recovery Strategies that are to be introduced under the Environment Act. These need to be closely watched over the coming years.

The third tier, Landscape Recovery will be tested with 10 large-scale projects due to commence in 2022. Invitations to take part in this will be made later in 2021.

Whilst all this piloting is going on the Countryside Stewardship CS) scheme will remain open to new applications. The last application window will be in 2023 for a 1st January 2024 start date. The scheme will be ‘simplified for 2021’. Existing HLS and CS agreements that are coming to an end can be rolled-over until ELM begins.

Other Support

Various other new schemes are set out in the document;

Farming Investment Fund: (from 2021 to 2026) This is the ‘son of Countryside Productivity’. This is due to open in ‘autumn 2021’. Like the CPS there will be two tiers;

- Farming Equipment and Technology Find: a fixed rate of grant for specified items with application online

- Farming Transformation Fund: for high-value items. A two-stage process with an EOI then full application

Farm Resilience Scheme: (from 2021 to 2024) A pilot scheme is already running offering advice to farmers on how to cope with the changes ahead. This will be built on. The pilot ends in March and details of the new advice and support scheme will be published after that.

Farming In Protected Landscapes: (from 2021 to 2024) This is effectively a scheme for upland areas. It covers National Parks but also Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs). There will be both farm-level projects including environmental payments and business support, and projects at community scale. More details are promised in early 2021.

Slurry Investment Scheme: (from 2022 to 2025) Grants will be available to help farmers invest in stores that must have at least 6-months of capacity and an impermeable cover. Rates of grant are not yet set.

New Entrants Scheme: (from 2022 to 2024) The scheme is still being designed, but it looks like funding is more likely to be for things such as matching services rather than direct grants to new entrants themselves.

Skills and Training: (from 2022 onwards) Firstly, this will see an Institute for Agriculture and Horticulture set up that will be the professional body for farming. Also, a set of standardised Key Performance Indicators for each sector will be produced, in conjunction with the AHDB to facilitate benchmarking. In addition, there will be funding for Research and Development in agriculture under an Innovation and Research programme.

Animal Welfare: (from 2022 onwards) Details of this funding stream are still being worked on. However, the ‘Animal Health and Welfare Pathway’ will be designed during the course of 2021. It will offer support for disease eradication programmes, capital grants to farmers for measures to increase animal welfare above the statutory baseline, and a new payment-by-results scheme (to be piloted in 2023)

Tree Health Scheme: (piloted from 2021, fully launched in 2024) This will build on the Tree health grants under CS.

All in all, there is quite a lot to digest from the document. We will be providing further information as it becomes available.

We are conscious that the details of future farm support have been released rather piecemeal by the Government and have therefore put together a two page summary, outlining how BPS will be phased out over the next seven years and the funding streams which will be available during and after this transition. This will be a ‘living’ document and it will be updated shortly to include this new information. The summary can be found at https://theandersonscentre.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ag-Policy-Summary-Oct-20-TAC.pdf

If you are interested in getting a concise and unbiased commentary on the key issues affecting business performance in the UK agri-food industry, click on the link below for a 90-day free trial of Andersons’ AgriBrief Bulletin:

https://agribrief.co.uk/

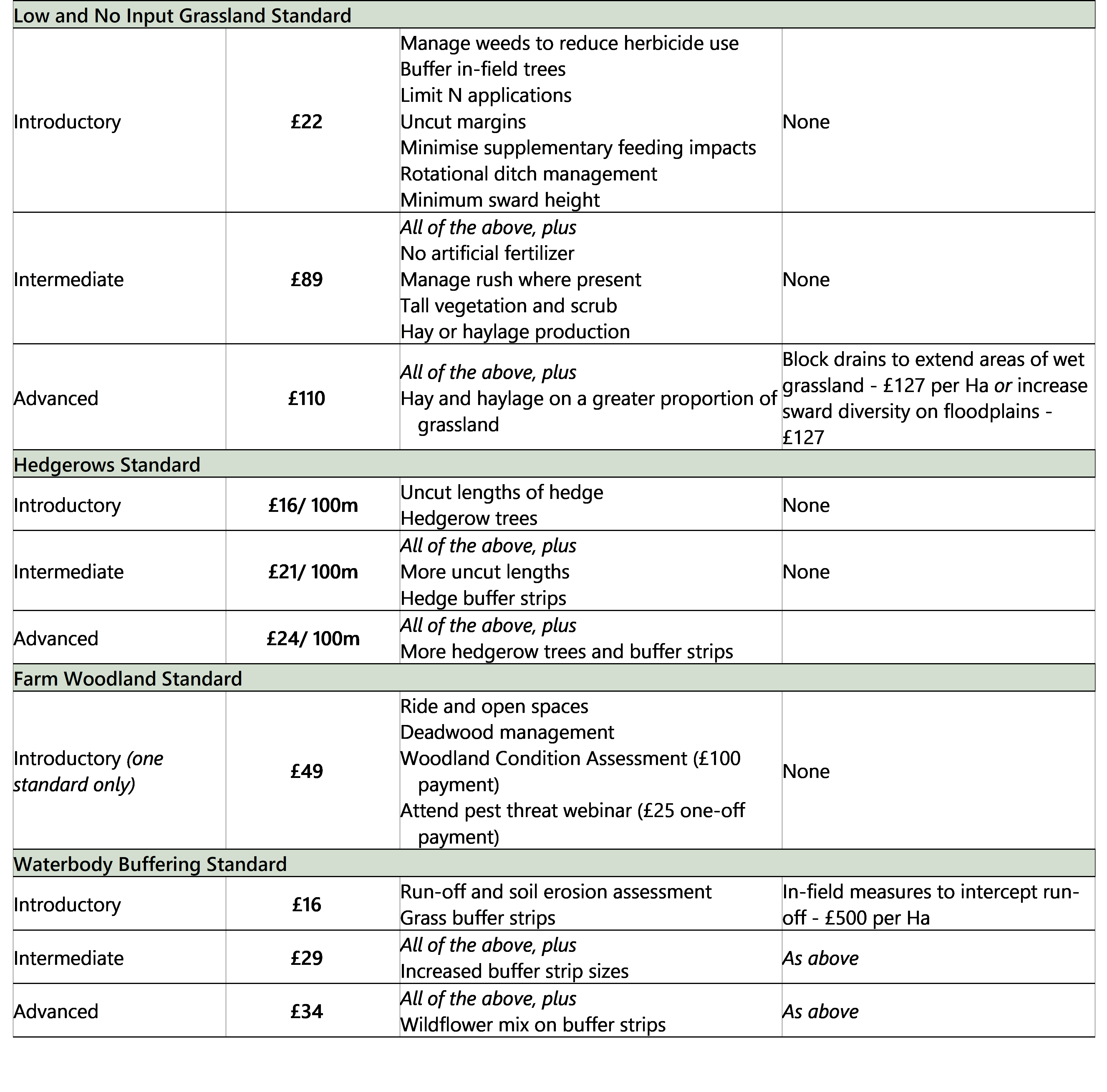

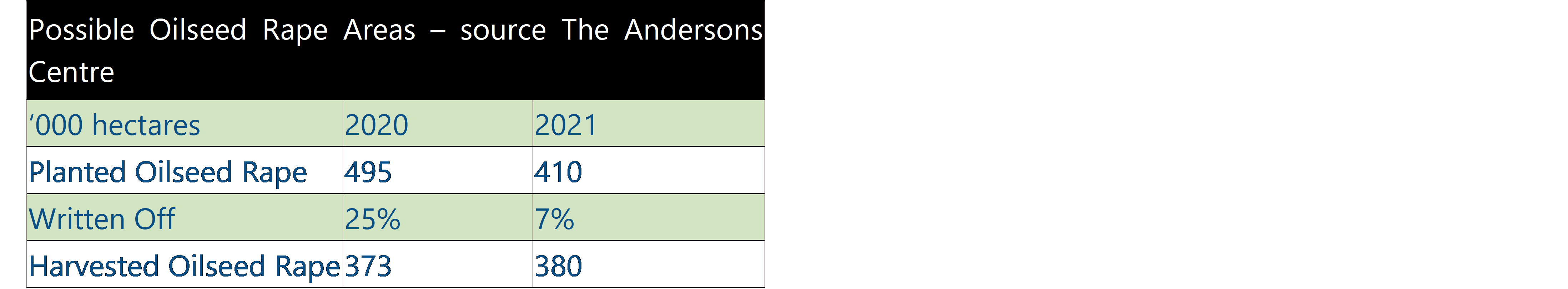

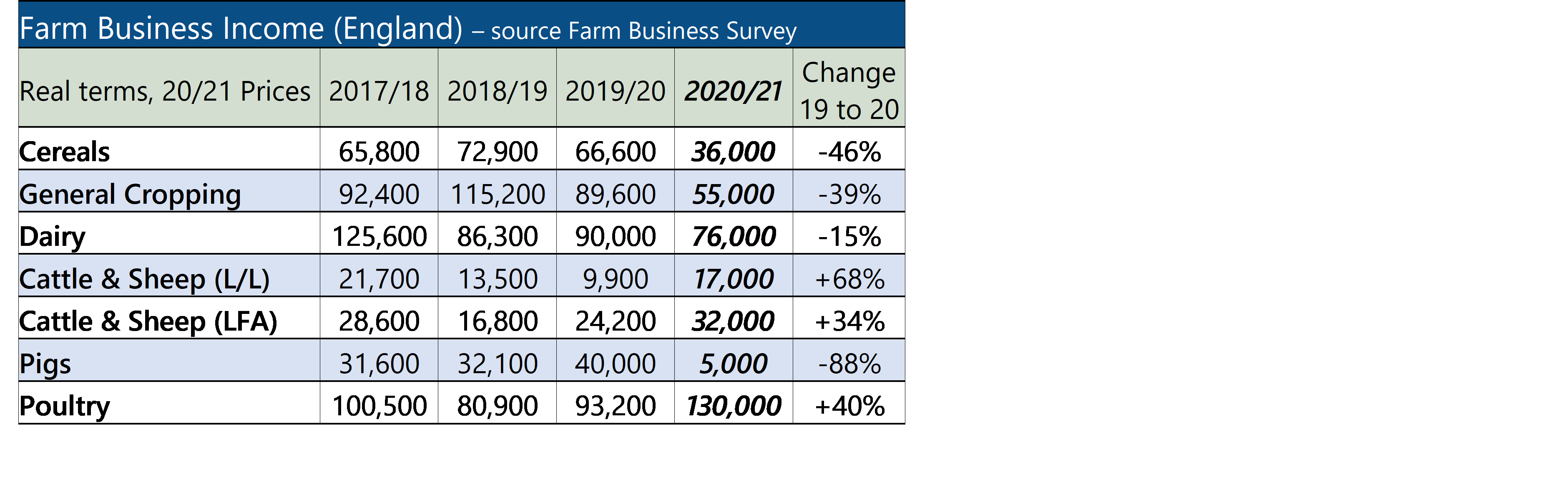

As seen in the table above, both Cereals and General Cropping farms are estimated to show big falls in FBI compared to the previous year. This is perhaps not surprising as the latest figures cover the 2020 harvest which saw reduced planted areas and lower yields. Dairy farm profits have been affected by higher costs, notably feed, even though milk prices were largely stable during the year.

As seen in the table above, both Cereals and General Cropping farms are estimated to show big falls in FBI compared to the previous year. This is perhaps not surprising as the latest figures cover the 2020 harvest which saw reduced planted areas and lower yields. Dairy farm profits have been affected by higher costs, notably feed, even though milk prices were largely stable during the year.